New research from Argonne National Laboratory and the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME) claims to have solved a battery mystery that has led to capacity degradation, shortened lifespan and, in some cases, fire.

In a paper published in Nature Nanotechnology, researchers uncovered some of the root causes and ways to mitigate the nanoscopic strains that can lead to cracking in nickel-rich lithium-ion batteries.

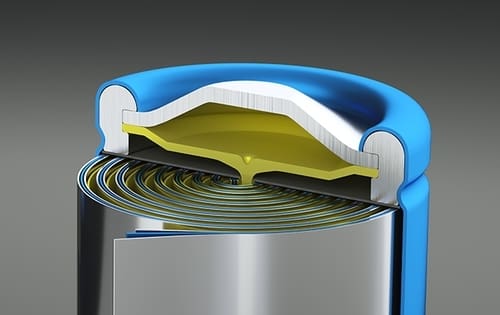

Because of the long-standing cracking issues in lithium-ion batteries that use polycrystalline nickel-rich materials (PC-NMC) in their cathodes, researchers over the last few years have turned toward single-crystal Ni-rich layered oxides (SC-NMC). But they have not always shown similar or better performance than older battery chemistries.

The new research, conducted by first author Jing Wang during her PhD period at UChicago PME through the GRC program, jointly supervised by Prof. Shirley Meng’s Laboratory for Energy Storage and Conversion and Amine’s Advanced Battery Technology team, revealed the underlying issue. Assumptions drawn from polycrystalline cathodes were being incorrectly applied to single-crystal materials.

“When people try to transition to single-crystal cathodes, they have been following similar design principles as the polycrystal ones,” said Wang, now a postdoctoral researcher working with UChicago and Argonne. “Our work identifies that the major degradation mechanism of the single-crystal particles is different from the polycrystal ones, which leads to the different composition requirements.”

As a battery containing a polycrystal cathode charges and discharges, the tiny, stacked primary particles swell and shrink. This repeated expansion and contraction can widen the grain boundaries that separate the polycrystals.

“Typically, it will suffer about five to 10% volume expansion or shrinkages,” Wang said. “Once an expansion or shrinkage exceeds the elastic limits, it will lead to the particle cracking.”

The day-to-day effect is capacity degradation. And if the cracks widen too much, electrolyte can get in, which can lead to unwanted side reactions and oxygen release that can raise safety concerns, including the risk of thermal runaway.

The study also challenged the materials used, redefining the roles of cobalt and manganese in batteries’ mechanical failure.

“Not only are new design strategies needed, different materials will also be required to help single-crystal cathode batteries reach their full potential,” said Meng, who is also the director of the Energy Storage Research Alliance (ESRA) based at Argonne. “By better understanding how different types of cathode materials degrade, we can help design a suite of high-functioning cathode materials for the world’s energy needs.”

Polycrystal cathodes are a balancing act of nickel, manganese and cobalt. Cobalt causes cracking but is needed to mitigate a separate problem called Li/Ni disorder.

By building and testing one nickel-cobalt battery and one nickel-manganese battery, the researchers found that, for single-crystal cathodes, the opposite was true. Manganese was more mechanically detrimental than cobalt and cobalt helped batteries last longer.

Cobalt, however, is more expensive than nickel or manganese. Wang said the team’s next step to turning this lab innovation into a real-world product is finding less-expensive materials that replicate cobalt’s good results.

Source: University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering